Links to various Aetna Better Health and non-Aetna Better Health sites are provided for your convenience. Aetna Better Health of California is not responsible or liable for non-Aetna Better Health content, accuracy or privacy practices of linked sites or for products or services described on these sites.

From the exam table to the kitchen table: A path to better health care

In 2018, Aetna launched an innovative program to address the behavioral and social factors that contribute to serious illness — and drive up health care costs. Central to the program are local care managers, who are embedded in the communities they serve. This is the story of one high-risk patient whose health was transformed with the help of her Aetna community care manager.

Two decades after being diagnosed with diabetes, Iliana Centeno started losing her vision, and then her kidneys began to shut down. She didn’t understand why. At 71, she still works and remains active, so she found it hard to grasp how these new issues were connected to her diabetes.

“I was taking medication, and I thought I was eating right,” Iliana says. “But I didn’t know what else I should do to take care of myself.”

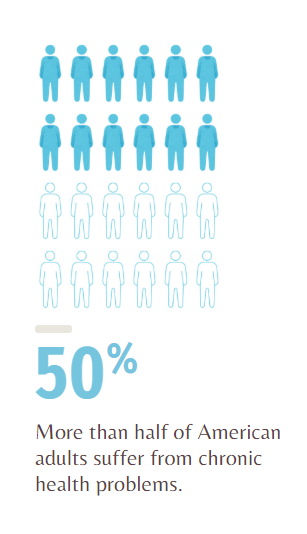

With more than half of Americans suffering from chronic health issues such as diabetes, heart disease or obesity, Iliana is not alone. But doctors today are limited in the amount of time they can spend with patients, and a patient may need more ongoing support than a doctor visit can provide.

Part of the problem is that the U.S. fee-for-service model doesn’t pay health care providers for preventive care and general wellness support. Indeed, services that can improve wellness — such as nutritional counseling, exercise programs and mental health services — are largely disconnected from the health care system, making them difficult for many people to access.

Since Iliana Centeno started meeting weekly with Maria Silva-Esquivel, a local nurse care manager, she has a much better understanding of how to manage her diabetes and other conditions.

Now, however, a new health care model is on the horizon, one that focuses on keeping people healthy rather than treating specific illnesses.

“The health care industry’s shift from ‘sick care’ to ‘well care’ has reached a tipping point — it’s no longer an industry ideal, but the norm,” says Karen Lynch, executive vice president of CVS Health and president of Aetna. “Outside forces, including rising health care costs, the growing sophistication of technology and predictive data analytics, and shifting consumer expectations will cement the industry’s transformation. But the success of the transformation will hinge on holistic and localized care.”

Health care should care for people before they’re sick

The need for change is clear from the troubled state of Americans’ health. Despite having the most expensive health care system in the world, Americans are less healthy and have shorter lifespans than citizens of most other developed nations. In 2017 the total cost of U.S. health care was $3.5 trillion — a massive 17.9 percent of national GDP, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. That amounts to $10,739 for every American.

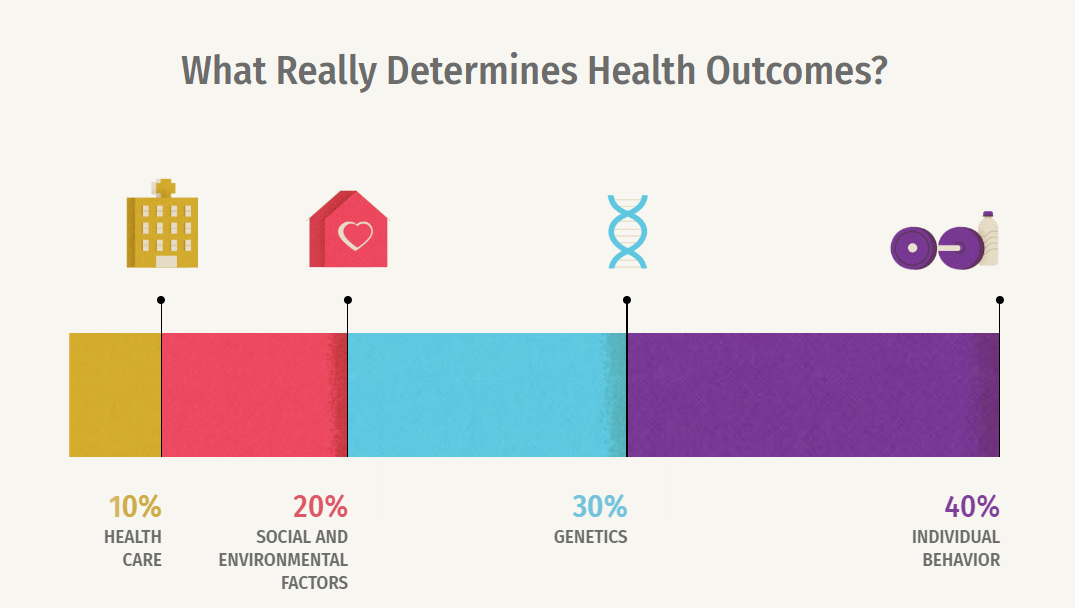

A better model recognizes that good health is more than just the absence of sickness. Health care alone accounts for only about 10 percent of a person’s health status, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation issue brief. Behavioral issues, such as smoking, alcohol intake, poor diet and lack of exercise, account for 40 percent. Social factors, like income and education, and environmental factors, such as where you live and your access to clean drinking water, are responsible for 20 percent. And genetics determines the other 30 percent.

This is why spending more on medical care does little to fix widespread health problems that stem from behavioral, social and environmental causes. A system to truly help Americans live healthier lives would connect them with a full range of health and social services, including care managers to answer their questions and join them in their journey to renewed vitality.

A personalized approach brings health care home

The goal of this shift to personalization is a system that addresses more than just the symptoms a patient mentions at the doctor’s office. This includes looking at everything from a person’s genetic history and mental health status to their diet, exercise and health goals — even issues such as where they live and their access to transportation.

“It’s hard to focus on your health when you’re worried about your housing situation. Research shows that providing safe and secure housing options can help improve health outcomes, particularly for individuals with chronic health conditions,” says Garth Graham, MD, vice president, community health and impact at CVS Health, and president of the Aetna Foundation. Care managers often help members find a shelter or arrange transportation to their doctor’s appointments — assistance that can help people avoid winding up in the emergency room.

Currently, the U.S. fee-for-service model doesn’t pay for preventive services or care coordination that can lead to better outcomes, thereby reducing hospital readmissions. But many providers, insurers and pharmaceutical companies are now experimenting with value-based care models that connect payment with positive outcomes, such as avoiding hospital stays.

To accomplish this, some health care providers and insurers are expanding the role of nurse care managers. “We support a person’s life outside of and between doctor’s appointments,” says Amelia Roberts, BSN, RN, CPN, a care coordinator based in Washington, DC, who runs a website called The Business of Nursing. “Now that payment models are shifting toward prevention of illness and hospitalization, the role has become more defined.”

Aetna Community Care, for example, is a program that employs nurse care managers, social workers and health educators who live close to residents and understand their communities. They can meet people face-to-face in their homes, shifting the conversation from the exam table to the kitchen table. If a doctor sees that a treatment isn’t working, the local nurse care manager can follow up, getting to know the person in their environment to learn why the treatment isn’t getting the expected results.

Each local pod is supported by a multi-disciplinary team of pharmacists, registered dietitians and mental health specialists who work with the care manager to address needs holistically across medical, social, financial and emotional spectrums. The team coordinates closely with physicians to support a customized treatment plan for the individual and caregivers.

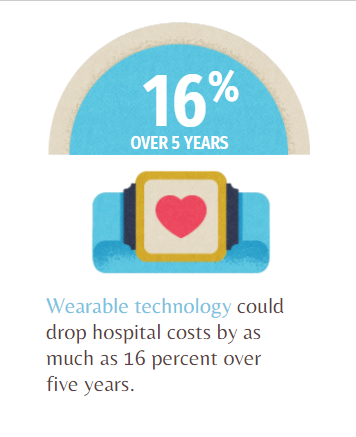

Thanks to advances in technology, people will have more frequent and convenient contact with their doctors and nurse care managers, even from a distance. People will be able to check in with their doctors or care managers quickly and remotely — without having to travel or take time off from work for an appointment every few months. Meanwhile, wearable health-tracking devices, or disease-specific solutions, like implantable blood-glucose monitors, can provide real-time health information beyond the snapshot of monitoring patients in a clinical setting. This enables doctors and patients to craft more personalized and effective treatment plans.

These advances have the added benefit of reducing health care costs. A study by Vitality Group found that the use of wearable health-tracking devices alone could help cut hospital costs by up to 16 percent.

Partners join the journey to better health

Empowering local personal-care teams to address not only the health needs but also the social needs of patients is the key to better outcomes for both patients and their families. “This approach, along with connecting patients with community resources that can help address some of the barriers to successful care, is a powerful formula for improved clinical quality and quality of life,” says Jean Bisio, RN, vice president of Aetna corporate care management.

For example, if a man is feeling depressed or isolated following a diagnosis of prostate cancer, the nurse care manager can connect him with a therapist or support group.

Maria enjoys visiting patients, such as Iliana, to help educate them on how to manage their health day to day.

“We have to try something different,” says Mark Calderon, MD, chief medical officer for Atlantic Accountable Care Organization and Optimus Healthcare Partners. “Doctors weren’t traditionally taught care-management skills in medical school, but as primary care doctors assume more value-based contracts, those skills, such as how to address social determinants of health, have to be learned.”

It was through Aetna’s Community Care program that Maria Silva-Esquivel, a local nurse care manager, contacted Iliana to help manage her diabetes and other conditions.

“The first thing I did was get her a glucometer that she could read with her vision impairment,” Maria says. “But she had trouble using it, so I taught her sister how to help her. Now Mrs. Centeno is able to check her blood sugar all the time.”

Maria enrolled Iliana in a diabetes education class and connected her with a nutritionist, who is helping Iliana make changes to her diet. And when Iliana explained that she was uncomfortable leaving home in the evenings, Maria arranged to pick up the class curriculum so she and Iliana could go over it together in her home.

Iliana says that simple act of listening to her concerns and providing the tools and solutions she needed made all the difference. “I always thought I was eating right and taking care of myself — until I saw how high that [blood-glucose] number was,” Iliana says. “Thanks to Maria, now I understand how everything is connected, and I finally have my blood sugar under control. I am thankful to everyone involved in my care.”

Images: Illustration by Script & Seal, Photography by T Brand Studio

Sources: CDC, CDW Healthcare, Aetna, New England Journal of Medicine, CMS, Health Affairs